It was Widow Pickersgill and her 13 year-old daughter Caroline who made the flag. They made it on the floor of the town brewery, the only place big enough to spread out the enormous banner. Four hundred yards of English woolen bunting formed the stripes, the stars, each measuring two feet from point to point, were made of cotton, and the women often stayed up until midnight sewing.

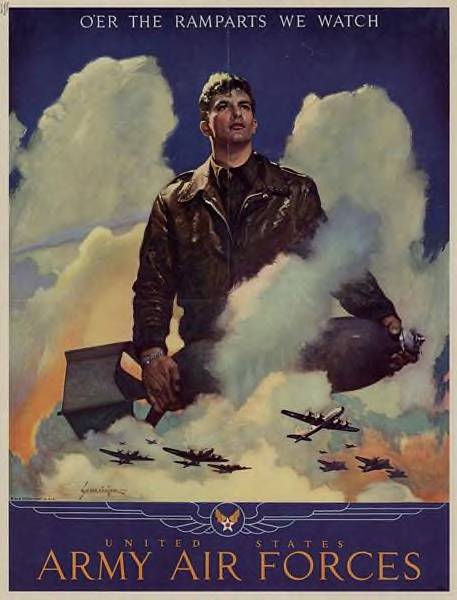

Fort McHenry in the city of Baltimore was expecting an attack from the British fleet any day. Over its ramparts, the widow’s flag flew, with all of its fifteen stars and shining glory, awaiting the sight of English vessels on the horizen.

In late August, 1814, whisperings filled the city. It had been heard that enemy soldiers had entered Washington, burning the Capitol and the White House. Baltimore, everyone thought, would be next.

Dr. William Beanes of Georgetown was imprisoned on the British warship Tonnant. He was accused of unfriendly acts towards British soldiers, and his townsmen were certain that he would be hung. In an effort to save him, they enlisted the help of young local lawyer Francis Scott Key, and his friend Colonel John Skinner. The two men set out in a small, unnamed boat flying the white flag of truce, armed with letters from captured British soldiers who detailed how kind Dr. William Beanes had been to them. As Francis Key and John Skinner passed Fort McHenry, the widow’s flag, 30-feet by 42-feet, was proudly flying.

Dr. William Beanes of Georgetown was imprisoned on the British warship Tonnant. He was accused of unfriendly acts towards British soldiers, and his townsmen were certain that he would be hung. In an effort to save him, they enlisted the help of young local lawyer Francis Scott Key, and his friend Colonel John Skinner. The two men set out in a small, unnamed boat flying the white flag of truce, armed with letters from captured British soldiers who detailed how kind Dr. William Beanes had been to them. As Francis Key and John Skinner passed Fort McHenry, the widow’s flag, 30-feet by 42-feet, was proudly flying.

Once aboard the Tonnant with the intention of negogiating for Dr. Beanes’s freedom, the Americans overheard too many details about the impending attack on the city of Baltimore, and were suddenly prisoners themselves. Dr. Beanes was officially released, but all three men were held on the smaller ship Surprise until the attack on Baltimore should be completed. Days passed, and they grew restless, waiting.

On the dawn of September 13, Francis Scott Key watched the attack on Fort McHenry. New British bombshells exploded into shrapnel after rocketing for 2 1/2 miles, leaving red streaks in the dark sky. As these rockets periodically lit up the night, Key and Skinner watched anxiously from the deck of Surprise for the 15-star flag. Every time, they saw it waving proudly there. For 25 hours the shelling went on. Hundreds of foot soldiers and a violent naval attack beat down on Fort McHenry, and still the battle went on. And then, it stopped. Everything was deadly silent. Through the smoke, Francis Scott Key watched, straining his eyes for a glimpse of the American flag.

As the first light of dawn filled the sky, Francis saw the flag. His heart swelled. All night long words had been going through his mind, the words of a poem. Now, using an old envelope from his coat pocket, he scribbled down some of these words.

The British soldiers returned in defeat, and let their prisoners free. The courage of General Armistead and his men at Fort McHenry had convinced them that the price for defeating Baltimore would be too great. Four months later, the Treaty of Ghent was signed: the War of 1812 was over.

The three men began the five-mile course upstream to Baltimore, and went to Old Fountain Inn for the night. Dr. Beanes and Colonel Skinner quickly fell asleep, but Francis Scott Key ordered paper and ink. He wrote down four verses, words which later became The Star-Spangled Banner, our national anthem.

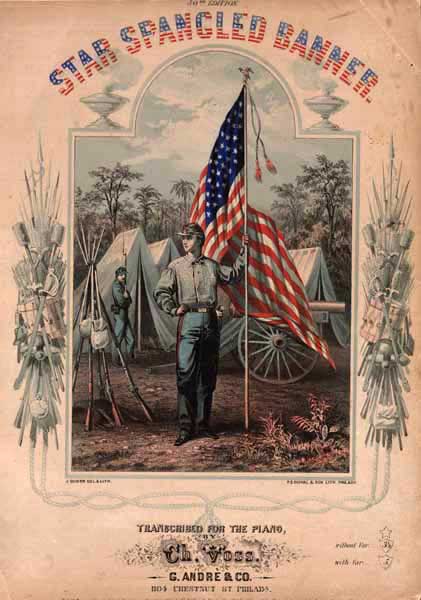

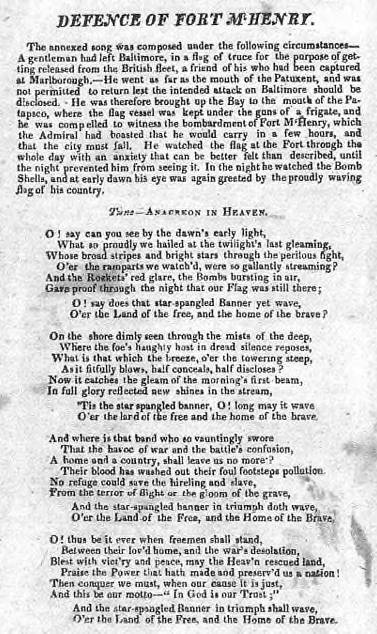

His brother-in-law, Judge J.H. Nicholson, took the poem to the printing office of the Baltimore American. Fourteen-year-old Samuel Sands was minding the shop in the absence of the men, who were fighting. He printed the poem under the title The Defense of Fort M’Henry on handbills. It soon became popular all over America, sung to the tune of To Anacreon in Heaven, a popular song of that era.

Congress named it our national anthem in 1931, but even before that this song helped America to identify proudly with its flag as a symbol of freedom; embodying what is good in our nation. The original star-spangled banner made by the Widow Pickersgill hangs in the National Musuem of American History at the Smithsonian in Washington.

This song will always be sung in the land of the free, the home of the brave.

Original 1814 broadside, “The Defence of Fort M’Henry”

Resources:

- A Children’s story about Flag Day -“The Star-Spangled Banner” by Eva March Tappan http://www.apples4theteacher.com/holidays/flag-day/short-stories/the-star-spangled-banner.html

- “The Writing of The Star-Spangled Banner” http://www.tc-solutions.com/croom/ssb.html

- “Facts about the United States’ National Anthem” http://www.ed.gov/about/offices/list/os/september11/ssbfacts.html?exp=0

- “The Story of the Star-Spangled Banner” by Natalie Miller, Cornerstones of Freedom, Childrens Press, Chicago, (c) 1965

- “The Star-Spangled Banner: The Story of America’s National Anthem” http://www.awesomestories.com/history/spangled_banner/spangled_banner_ch1.htm

- “The Star-Spangled Banner at American History Musuem” http://americanhistory.si.edu/ssb/

October 20, 2011 at 4:30 am

cruises fort lauderdale…

[…]The Star-Spangled Banner « Home of the Brave[…]…

October 28, 2011 at 10:11 am

celebrity rehab ,celebrity cruises ,celebrity net worth ,celebrity gossip ,celebrity news ,celebrity look alike ,celebrity birthdays ,celebrity deaths ,celebrity deaths 2011 ,celebrity baby names…

[…]The Star-Spangled Banner « Home of the Brave[…]…

January 28, 2012 at 2:23 am

Diamond Ranch Academy employment, staff at diamond ranch academy, Diamond Ranch academy school…

[…]The Star-Spangled Banner « Home of the Brave[…]…